My Journey replacing Promises with RxJS

This is a guest post by Dzhavat Ushev. He’s a front-end developer, who uses web technology to solve problems. I met Dzhavat at ngVikings in Helsinki this year! A couple of weeks ago I found him asking for help about an RxJS problem on Twitter and followed up on some discussions he had with others to solve his specific issue. That’s when I asked him to write down his learnings as a guest post. Enjoy 🙂!

Before diving in I’d like to give you some context and the reason for doing this refactoring.

I’m working on an Angular app that uses Microsoft’s Graph and SharePoint APIs to get/create/modify data. This means that we make a lot of requests. To do that we’re using the excellent HttpClient service build into Angular. This makes it very easy for us to send a request by using methods like get(), post(), patch(), etc. One important detail, however, is the fact that all of these methods return Observables. Early on in the development of our app we decided to convert these Observables to Promises because we didn’t have much experience doing things “reactively”. So we ended up treating all of the requests we’re making as Promises.

Then some time passed by and we got brave enough to try a bit of RxJS here and there but mostly related to handling resize and scroll events. Then a few months ago we realized that it was about time to “stop swimming against the stream” and embrace the idea of handling HTTP requests as Observables as well. So we’ve been slowly refactoring our code towards using RxJS Observables.

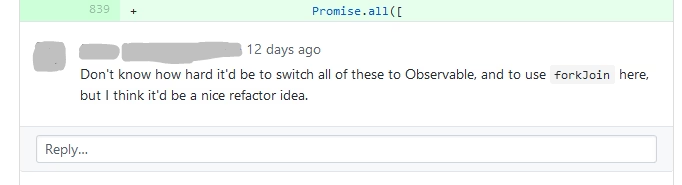

One day, after submitting a new pull request, I got this comment in my code review:

Aaaand that’s where my adventure begins 🙂

Promise land

The method I was going to refactor looked pretty much like this. Let’s call it createFolder just for the sake of giving it a purpose.

createFolder() {

Promise.all([ // 1

this.makeRequest('1'),

this.makeRequest('2'),

this.makeRequest('3')

])

.then(() => this.makeRequest('get-id')) // 2

.then(id => { // 3

if (id.length > 0) {

return this.makeRequest(`call-1-using-${id}`)

.then(() => this.makeRequest(`call-2-using-${id}`));

}

})

.then(response => console.log('All done!')) // 4

.catch(error => console.error(error));

}

As you can see, I’m making a bunch of request and all of them are treated as Promises. Some are called in parallel, while others wait for a result to come in before calling them in sequence.

Here’s a brief overview of how the code works:

Promise.all()takes an array ofPromises and executes them all at once (in parallel). It will wait until all of them are resolved before continuing down the chain. In my case I’m making three simple requests. Once they are done, the code will continue to the firstthen()passing no response to it.- From the first

then(), I’m returning anotherPromisethat makes a request to get me a specialidwhich I’m going to need later on. Once this request is done it will pass the value to the secondthen()in the chain. - Inside the second

then()I have a simpleifstatement to check whether theidhas some value. If it has, I’m returning twoPromises chained one after the other in order to run them in sequence. This introduced a bit of nesting but I was ok with that. - Finally, the last

then()will wait for the requests to complete and it will log'``All done!``'to the console.

Note: If the id value in step 3 doesn’t pass the if check, the code will immediately run the last then() in the chain resulting in undefined as a response.

At this point I thought for a moment and said to myself: “I can probably refactor this rather quickly by nesting Observables but that is surely not a proper way to do it. I have to find a better way that takes advantage of RxJS’ build in operators. And I need to understand what every step is doing so I can apply this in other cases as well!”

Realizing I need help

As I mentioned above, I gained some experience working with RxJS but that is mostly related to a single Observable - a single request, a stream of scroll/resize/click events, etc. Here I not only needed to handle multiple Observables running in a specific order, but also use a bunch of operators that would keep the structure as flat as possible.

The first thing I did was to open the documentation and browse through some of the operators. The examples there were easy to follow and understand. What I struggled with was gluing things together.

So I did what everybody should do in this situation - raised my hand and asked for help!

#RxJS help 🙋♂️I have this moster function which uses Promises and need to refactor it to using observables instead. I know I can use `forkJoin` for replacing `Promise.all` but then how should I go about the rest w/ nesting too much. (Stackblitz https://t.co/SM89MUyfsR) ❤ pic.twitter.com/WlMJGGa8Yz

— Dzhavat Ushev (@dzhavatushev) September 12, 2018

I got some really helpful suggestions from @chaos_monster and Dominic Elm on Twitter. They pretty much solved the problem for me so the credit should fully go to them.

RxJS land

After playing with the proposed solution (shown below) for some time I started to understand it. Everything made sense and I could follow the logic all the way through.

createFolder() {

forkJoin([

this.makeRequest('1'),

this.makeRequest('2'),

this.makeRequest('3')

]).pipe(

mergeMap(() => this.makeRequest('get-id')),

filter(id => id.length > 0),

mergeMap(id => concat(

this.makeRequest(`call-1-using-${id}`),

this.makeRequest(`call-2-using-${id}`)

))

).subscribe(

() => {},

error => console.error(error),

() => console.log('All done!')

);

}

So the rest of the post will be dedicated to explaining how the code works and how each part maps to the different parts of the Promise based method from the example in the beginning.

forkJoin

This operator works pretty much the same way as Promise.all(). It accepts any number of Observables passed in directly or as an array. It will wait for all of them to complete and combine the last values they emitted.

Promise.all([this.makeRequest('1'), this.makeRequest('2'), this.makeRequest('3')]);

// ↑ became ↓

forkJoin([this.makeRequest('1'), this.makeRequest('2'), this.makeRequest('3')]);

This was fairly easy!

Now, if I wanted to just make three requests and move on, I would have called subscribe() here passing to it next(), error() and complete() functions.

But since I wanted to do more, I had to do some extra work.

pipe

This little fellow is quite useful.

Starting from v5.5, RxJS shipped “pipeable operators”. Without going into too much details, a “pipeable“ operator is just a function that takes an Observable as an input, performs some action on it, and returns a new Observable as an output. This new Observable is then passed as an input to the next operator and so on until it eventually reaches the subscribe() method at the end.

The pipe() method is what makes this possible. It basically allows you to combine operators.

Let’s see how that solved my problem.

mergeMap

Things started to get serious. mergeMap (and it’s cousins) was one of those operators that no matter how much I read about, I still felt unsure when and how to use.

With that in mind, let me try to explain it.

In order for mergeMap() to work we actually need two Observables. Let’s call the first one “source” and the second one ”inner”. Every time the “source” observable emits a value, mergeMap will capture it, pass it on to the “inner” observable and wait for the “inner” observable to emit something. When it does, it will capture this new value and will merge it back to the “source” observable.

Applied to my case, it looked like this:

Promise.all([ ... ])

.then(() => this.makeRequest('get-id'))

.then(id => {

// use id ...

});

// ↑ became ↓

forkJoin([ ... ])

.pipe(

mergeMap(() => this.makeRequest('get-id'))

).subscribe(id => {

// use id ...

});

Whenever forkJoin() emits a value, mergeMap() will start a new request for getting an id. When the request is done and the the inner observable emits the id, mergeMap() will grab it and merge it back to forkJoin(). Since there are no more operators the id will be passed to subscribe().

filter

The next step in the process was to handle the second then(). This step can be split into two parts. The first is the if check and the second is the two Promises that are returned in case the if check evaluates to true.

The first part can be handled quite easily by using the filter() operator.

This operator works the same way as the filter() method on arrays. Its purpose is to keep/discard values. It takes a function that evaluates each value emitted by the source Observable (in my case that is the Observable coming from mergeMap()). If the evaluation returns true, the value is emitted, if false the value stops there and is not passed to the output Observable.

With that in mind my code now looked like this:

Promise.all([ ... ])

.then(() => this.makeRequest('get-id'))

.then(id => {

if (id.length > 0) {

// use id ...

}

});

// ↑ became ↓

forkJoin([ ... ])

.pipe(

mergeMap(() => this.makeRequest('get-id')),

filter(id => id.length > 0)

).subscribe(id => {

// use id ...

});

It’s worth mentioning here that the next() function inside subscribe() will receive the id value only if it passes through the filter(). In case the id doesn’t make it through the filter(), only the complete() function will be called.

concat

The second part of the second then() was about handling two requests running in sequence. The order was important that’s why I ended up using two Promises chained together. When the second Promise resolves, the last then() in the chain will be called and that’s how I knew that everything is done.

So in order to achieve this behavior of two requests executed in sequence, I ended up using concat(). According to the documentation:

It concatenates multiple Observables together by sequentially emitting their values, one Observable after the other.

Exactly what I was looking for!

The only problem was that the concat() is not an operator*, so I could not simply put it after filter().

There is actually a

concatoperator but it is deprecated.

mergeMap again

The trick was to use mergeMap() once again. This operator would wait for filter() to emit something, and when it does, it would take the value and pass it on to concat(). The concat() on the other hand will subscribe to the first observable and it will wait for it to emit something. When it does, the value will be send back to mergeMap(), which will merge it into the outer Observable, and from there on it will travel all the way down to subscribe().

Put in practice:

Promise.all([ ... ])

.then(() => this.makeRequest('get-id'))

.then(id => {

if (id.length > 0) {

return this.makeRequest(`call-1-using-${id}`)

.then(() => this.makeRequest(`call-2-using-${id}`));

}

})

.then(response => console.log('All done!'));

// ↑ became ↓

forkJoin([ ... ])

.pipe(

mergeMap(() => this.makeRequest('get-id')),

filter(id => id.length > 0),

mergeMap(id => concat(

this.makeRequest(`call-1-using-${id}`),

this.makeRequest(`call-2-using-${id}`)

))

).subscribe(

response => {},

error => console.error(error),

() => console.log('All done!')

);

The final All done! message will be printed to the console when both Observables inside concat() complete.

Again, one thing worth emphasizing here is that the second mergeMap() will not run if the id inside filter() doesn’t pass the condition. In that case you’ll still see All done! printed to the console but that is because it is located inside the complete() callback which is always invoked. Two requests inside concat(), however, would never have been called. So keep that in mind.

Conclusion

Phew! That was a lot. And this doesn’t even cover what happens if a request fails. That’s something for you to try. It’s important so remember to handle that case.

I personally learned a few things here:

- Breaking a complicated problem down to smaller parts is important because they feel easier to solve.

- Being stuck and not knowing how to solve a problem can be a good thing because it helps you realize that there’s an opportunity to learn and grow.

- There’s no shame in asking for help. We should do it more often.

- Sharing what we know can help someone. We should do it more often as well.

- I’m probably over explaining some stuff :smiley:

Have you had to make a similar refactor? How did you do it? How would you improve my solution? Post your comments below.

If you’ve made it thus far, thank you for reading! Hope you learned something new.

Thanks to Juri for reviewing this post (and encouraging me to write it in first place).